Online child sexual abuse is not a new problem, but it is a rapidly growing one. The methods abusers use are constantly shifting and changing, and they are always looking for ways to avoid detection. This section tells you what you need to know about how serious this problem is, and why you need to act now, not later.

When a child or young person (anyone under 18) is sexually abused, they’re coerced or tricked into sexual activities. The child might not understand that what’s happening is abuse or that it’s wrong. It could happen offline, with images and videos of this abuse then shared online, or the abuse could happen online.

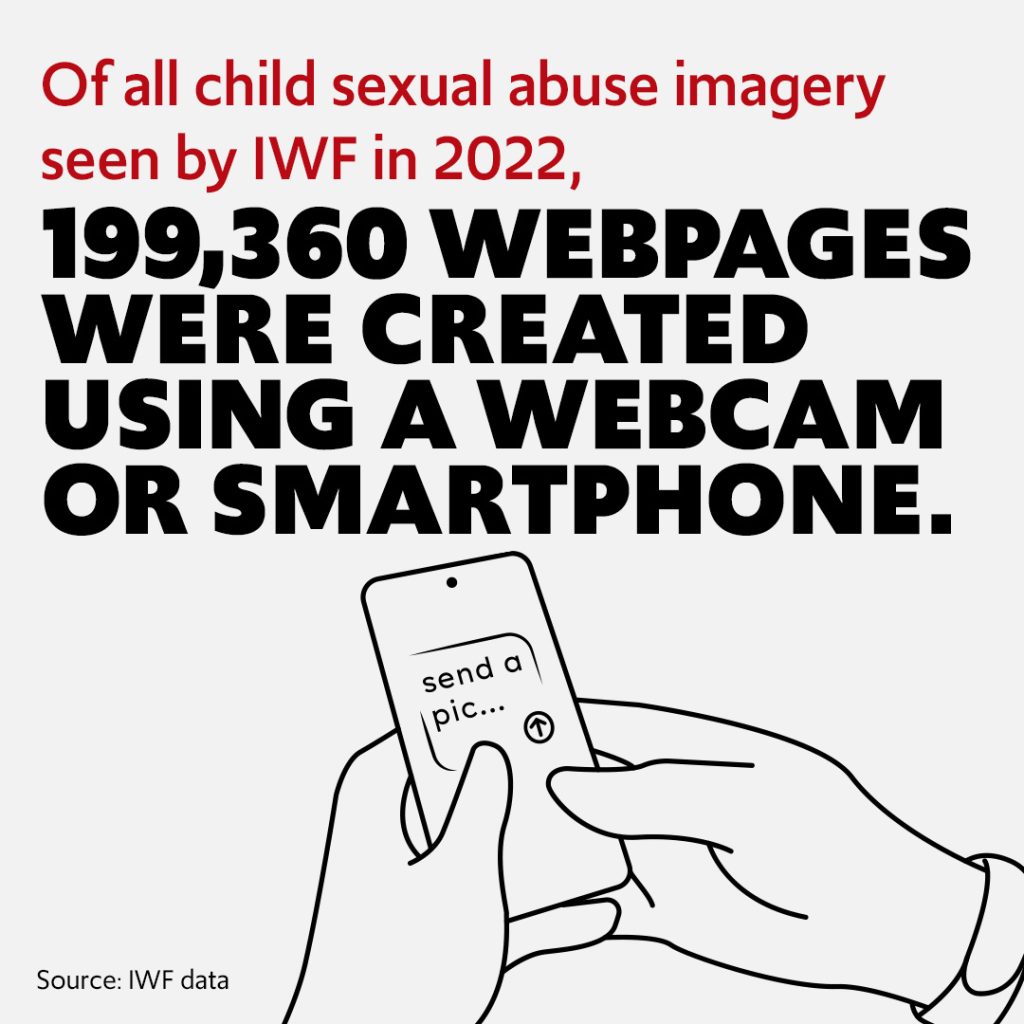

‘Self-generated’ online child sexual abuse content is created using any device with webcams and cameras, and shared online via a growing number of platforms. In some cases, children are groomed, deceived or extorted into producing and sharing sexual images or videos of themselves. Sometimes children are livestreaming and may not know they are being recorded. Children are never to blame when they’ve been coerced or tricked into capturing their own abuse. They may be completely unaware that the ‘friend’ they’re talking to online is an adult abuser and is secretly recording the abuse.

The images and videos primarily involve girls aged 11 to 13 years old, in their bedrooms or another room in a home setting. When much of the world was subject to periods of lockdown due to COVID-19, the volume of this kind of imagery grew significantly.

This kind of child sexual abuse is a huge problem, and it’s increasing.

Here are some figures which might help you understand the scale of the problem:

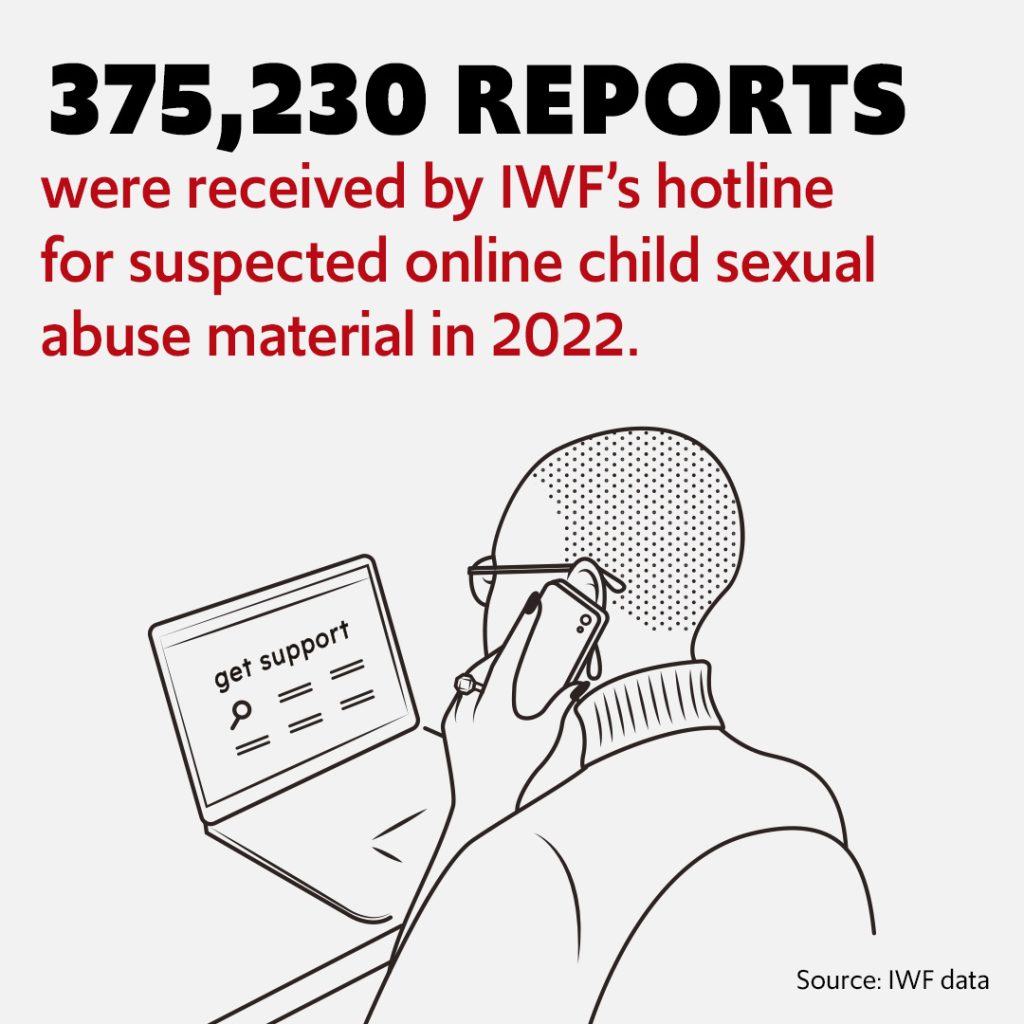

IWF’s hotline for reporting suspected online child sexual abuse material assessed a record number of reports in 2022: 375,230.

Of all the child sexual abuse material identified by IWF in 2022, more than three quarters was created by offenders grooming and encouraging the children to behave sexually over a webcam or live-stream.

This kind of child sexual abuse is a huge problem, and it’s increasing.

Here are some figures which might help you understand the scale of the problem:

Of all the child sexual abuse material identified by IWF in 2022, more than three quarters was created by offenders grooming and encouraging the children to behave sexually over a webcam or live-stream.

Being online can offer great benefits and opportunities for all children, including those with special educational needs and/or disabilities. It can connect them with others, and support learning and the development of cognitive, communication, social and emotional skills. 86% of autistic teens and 82% of teens with learning difficulties believe the internet has opened up possibilities for them (versus 62% of children without SEND).

Every child has a unique set of needs. The way they experience the world, and the extent to which they are vulnerable to adverse life experiences, will also differ. However, there are some key factors that can make SEND children more susceptible to online abuse.

LGBTQ+ is a term that includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and questioning/queer people, but also encompasses a wide range of gender or sexual identities.

The internet can offer a sense of community for LGBTQ+ young people, providing them with an opportunity to find out information about topics that they might not feel comfortable discussing with friends or family, or to connect with people who are in similar situations.

These young people may be looking to make meaningful connections with others online, whether they are looking for friendship, advice, or looking to make a romantic connection. While all young people are potentially at risk of online child sexual abuse, LGBTQ+ young people may be targeted because of their gender or sexual identity. Almost 1 in five (18%) LGBTQ+ young people have experienced some form of sexual abuse, compared with 1 in 10 (11%) of non-trans [cis] heterosexuals. They might also be using sites or apps that may be designed for adults, but which have a specific LGBTQ+ section that might be the only place they can find other LGBTQ+ people. Stonewall found that more than 1 in 5 LGBTQ+ young people under the age of 18 have used adult dating apps and more than 2 in 5 have sent or received sexual, naked or semi-naked photos to or from a person they were talking to online.

You can support LGBTQ+ young people by taking a few simple steps to help keep them safe. Talk to your child and keep the conversation open and honest. Learning about your child’s gender or sexual identity and having an open conversation about their identity can help you both understand more about the benefits and risks of being online as an LGBTQ+ young person. Abusers may try to pressure or threaten LGBTQ+ young people by saying they will ‘out’ them to others, so having an open conversation about their identity is a key part of talking to your child about their online activities and establishing trust.

LGBTQ+ young people might discuss or explore their gender or sexuality online]. It’s important to talk to them about the importance of not oversharing on the internet or responding to comments or messages from people online who ask for explicit content.

Find out about what they enjoy on social media and talk to them about any communities they have found online. Some communities might be unmoderated, so helping them find age-appropriate pages or forums from recognised charities or groups can help ensure that groups they join have added protection from harassment or abuse. Groups like The Mix provide moderated discussion boards that allow LGBTQ+ young people to connect in a safe space.

Additional resources and support:

There’s a big increase in sexual images and videos (recorded and live-streamed) that have been created of children as a result of an abuser grooming, manipulating, deceiving or coercing a child into sexual activity over a webcam. This means less risk for the abuser: they have no physical contact with the child. Often, the child does not fully realise or understand what they were doing, or why.

With live-streaming, children may not know that the person watching can screen capture or record a video, and upload that material somewhere else for other people with a sexual interest in children to see.

This kind of abuse is different to sharing nude selfies among peer groups, ‘sexting’, or being encouraged to perform a sexual act for someone who is physically present.

In all cases of sexual abuse, the adult grooming the child for the material is the person responsible for it: the child is never to blame.

It’s important to ensure that children understand it’s never their fault they were sexually abused.

It’s creepy old men, alone in their bedrooms, pretending to be teenagers.

Many online abusers are much younger than you might have thought and are very socially active. They come across as ‘normal’, friendly and approachable. Some are open about their age and identity.

This method of abuse isn’t happening in dark, hidden corners of the web, but in plain sight, on platforms and apps used by children and their parents.

When offenders have made contact, abusers will encourage, coerce and manipulate children into sexual activities and then capture that as a recording. They use image hosting sites and cyberlockers (secure file sharing services) to store and distribute the material. The time between first contacting a child to distributing material can be just a few minutes, or hours.

My child is safe at home with me – nothing’s going to happen here.

Self-generated online child sexual abuse often happens when children are at home, in their bedroom, behind a closed door, sometimes with other family members at home.

I would notice if there was anything wrong.

Not all children realise they’re being abused, and others feel too ashamed to say anything. There is no guarantee you would know anything had happened to your child, unless they tell you.

Abuse and grooming happens over weeks, months or years.

The gap between an abuser asking and a child responding can be just a few minutes.

Although some abusers might use well-known grooming methods such as giving children attention and compliments, or chatting with them to form a relationship, others use a more scattergun approach – they just make contact with hundreds of children, and some respond.

The abuser may then groom a child by suggesting more and more explicit acts: “Pose for the camera.”; “Do a silly dance.”; “That’s great, but it would be even better if you take your PJ’s off/try that without your knickers on.”; “I dare you to…”; “Let’s play a game!” The child may not fully understand what they are doing, or what they’re being asked to do might not seem that unusual. What is clear though, is that this is abuse and never about a child consenting.

Unfortunately, some abusers are now persuading children to involve their siblings in this abuse. Much younger children – some as young as 3 – are being included in the creation of sexual content with their older brothers or sisters.

Any child, no matter what their background or situation might be, who has unrestricted access to internet-connected devices is at risk of this abuse happening to them. No-one is immune.

However, evidence shows that it happens to girls much more than boys, and most often girls aged 11 to 13 years old. It’s helpful to understand some reasons for this, to realise why just banning a child from using social media is not the answer or won’t solve the problem.

First of all, remember that for young teenagers, life off the internet is no more ‘real’ than life on the internet – both worlds are their reality. And just like offline life, online life can be full of positives. It’s where they can chat to their friends and stay connected (especially important during the isolation of lockdown). It’s where they can laugh and be entertained. It’s where they can find and share images and videos. It’s where they can argue their opinions and express themselves in ways that feel fun, exciting and carefree.

Online spaces are places where young people can feel empowered. They’re places that adults don’t totally ‘get’; where teens can create a private life for themselves separate from their parents and carers. This can be vital for their development and preparation for adult life.

Online sexual abuse only affects children from unstable or deprived backgrounds.

The IWF sees materials with all kinds of children from all kinds of backgrounds. Any child with unsupervised access to the internet is potentially at risk.

Young people of this age can care deeply about what others think of them and the content they post (which reflects who they are, or how they want to be seen). Likes and follows can be important, boosting their feelings of worth and self-esteem. For them, everything they do online is immediate, with instant feedback – they may not be thinking about where the content they create might end up in the future.

Many young people receive friend or follower requests from people they don’t know, and many view accepting these is part and parcel of being on social media. According to the UK Safer Internet Centre, 62% of 8 to 17s have received friend requests from people they don’t know. And recent research from the Office of National Statistics says that 1 in 10 children aged 10-15 have spoken to a stranger online.

Young people who do respond to messages and requests for explicit content may do it without fully understanding what they are being asked for, or as a way to gain likes or follows in return, thinking they are forming a relationship with the person asking.

Banning a child from using all social media – taking away their devices, making them delete their apps, or getting them to unfollow everyone they don’t know in person – isn’t the way to stop them being at risk. If you prevent them from accessing an essential part of their reality, and allowing them to connect with their friends, they will feel resentful, angry and alienated from you. They may also find other ways to keep connected, and become more private about their online lives.

Even if a child doesn’t know what they are doing, sexual abuse always has an impact. That’s true whether it happens once or many times, and whether a child takes their clothes off or leaves them on. A child can never consent to sexual abuse, regardless of how it took place. But they will have to live with the impact.

Our downloadable guide for parents and carers.